|

The conventional argument is that we need to promote girls' education

because there is an inverse correlation between the number of years of

schooling that mothers have had and the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in

the community. The higher the rate of literacy among women, the higher

the chances that the children will survive to adulthood and enjoy better

health. This argument is based on observed facts - the State of Kerala,

with a female literacy rate of 86 per cent, has an IMR of 19 whereas Orissa,

where the female literacy rate is around 30 per cent, has an IMR of 120

per 1,000 live births (the national averages are 45 per 1,000 live births

in the urban areas and 82 in the rural areas - again, confirming the theory

that mothers' illiteracy and high IMRs go together.

The comparable figures for East Asia are 18 and for the industrialised

countries 13, as per the latest Human Development Report of UN.

|

Therefore, the argument goes, get the girls into school and keep them there, and you will automatically improve the health status and longevity of their progeny. The problem is that it is not so easy to get all girls nationwide (or boys, for that matter) into school, much less keep them there beyond the primary stage because of the ground realities of poverty and lack of facilities and access (no resources for opening sufficient schools in the remote regions or to staff them, girls needed at home to look after younger siblings while the mother goes out to work to eke out a living, fear of sending growing girls out alone, etc). With the result that wide disparities in IMR continue between different regions of the country, in spite of some undeniable and spectacular progress made since independence.

Here is where the UNICEF report holds out hope for planners, NGOs and social activists, by spotlighting an alternative correlation. The report points out that in the State of Manipur where female literacy rate is just 48 per cent (vastly lower than in Kerala) the IMR is about the same as in Kerala.

If we draw a graph with female literacy rates along the horizontal axis and IMR along the vertical axis, and plot the different states of the country, a curious fact emerges - Kerala (female literacy rate of 86 per cent and IMR of 19) gets positioned at the southeastern corner of the graph, low down and farther to the right than any other state. Orissa occupies the diametrically opposite northwestern corner, way up and close to the vertical axis (literacy for female around 30 per cent, and IMR 120). Clustered between these two extremes are the rest of our states - Karnataka almost in the middle, close to the national average, all other large states like Madhya Pradesh, UP, Rajasthan and Bihar falling to the left, with lower female literacy rates and higher IMRs than the national average. In Rajasthan only 17 women out of every 100 can read and write. Manipur, by contrast, falls way down and to the left, with both IMR and literacy rate low.

The conclusion that UNICEF suggests is that it is not so much schooling per se that makes the difference, but what schooling causes - which is empowerment and a sense of self-confidence in women. An unlettered woman feels not only physically handicapped, but also psychologically diffident and vulnerable, but a Manipuri woman who may not be able to spell or read a newspaper, is part of a social pattern that does not leave women feel as oppressed as, say, a woman in Rajasthan. This sense of self-assertion, then, is the crux, not the number of years of schooling. Which means that we do not need to wait till we can build enough schoolrooms or blackboards, or enough creches so that girls can attend classes without having to worry about the care of their siblings.

This is not to belittle the value of education, of course. Far from it. However, the point is that even if we are not for the moment able to get all the girls into schools, that does not mean that we cannot empower them with a sense of self-worth, in the meantime.

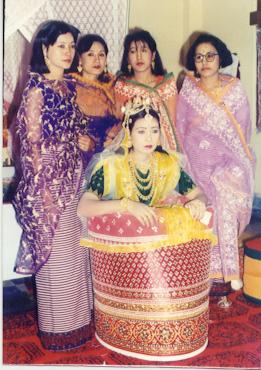

"The clue to better child survival conditions in Manipur can be found in the freedom that women of this State enjoy, particularly in respect of marital and occupational choices," says the report, adding that "women in Manipur face far less pressure to marry early and much less discrimination than in other parts of the country". The average age for marriage for Manipur is 23, and woman are valued for their economic contribution to the family and to society. Female work participation rate is, at 38 per cent, more than double that in Kerala. The central market in Imphal is even today entirely owned and controlled by women. Women play a major role in rice cultivation, too.

What is perhaps more important than the work participation rate or literacy figures, is the tradition of collective action that Manipuri women have. Nupi Lan is a word that translates as "women's war". In 1939, women of this tiny northeastern region organised an agitation against the British which came to be known as Nupi Lan. They held the British political agent confined for several hours, in spite of a bayonet charge by mounted police. The British could not conquer this region. During 1970s the women of Manipur rose again, this time to fight collectively, another battle - against alcoholism among the men. In what became famous as the "Night patrollers movement", woman in groups patrolled the streets after dark and either extorted a fine from men who had been found drinking or beat them up. They raided breweries and forced their closure. Earlier, in 1904 and 1925 too, women had resorted to collective action, against forced labour conscription and against arbitrary tax imposts respectively.

"The Manipuri story indicates that active participation by women in public affairs can and does contribute to better conditions for children and society at large", says the UNICEF report.

Schooling is a means of empowering the psyche of girls - but one does

not need to be able to solve simultaneous equations in algebra or memorise

the Latin names of the parts of a flower, in order to develop self-confidence.

|

If there is not enough money to extend schooling facilities to all

for the moment, we can still address the question of developing group strength

and assertion, through non-conventional methods. Poor and illiterate women

too, can be assertive - and by taking charge of their lives, enable a lowering

of the IMR, as the women of Manipur have shown.

[29 December 1996 Deccan Herald, Bangalore] From the above, it is clear that Manipuris are ahead of other Indian

communities in terms of promoting and practicing equal rights for men and

women. Literacy, by definition and in modern education system, may

mean for someone to be able to attain school and be able to read or write.

However, Manipuri life and social customs are a continuous process of learning

which provides the very essence of existence in harmony. Below I furnish

some of the reasons, in addition to those pointed out above, why Manipuri

children have a better chance of living than the children of other Indian

communities with equal or higher economical and educational facilities.

The marriage system as well as prenatal and postnatal mother and childcare

processes practiced by Manipuris are the reasons for having lower IMRs

among Manipuris.

|

1. Freedom to choose and to be able to practice it is the highest form of democracy in any society. A Manipuri girl may pursue any profession she likes, and she can marry a lover of her own choice without any objection from their parents or others. This has two advantages: first, a woman (or a man) can't blame their parents or anybody for spousal differences or incompatibility, if any, found out later on, since it was their own choice; and secondly, love has no boundary for caste and creed. Parents too can't demand dowry from either side, and expenses are more or less equally shared. A girl's parents and brothers may provide as much as or as little as they can afford to as gifts for their daughter or sister in marriage. Dowry and the caste system are the most dangerous elements for destroying human health and relationship, specially for women, among the Indian communities. Manipuri society is distinct from other Indians in its social customs.

2. Once married, a pregnant woman is considered to attain the most beautiful stage of her life just like a flower in full bloom. This provides a woman the internal strength and moral uplifting, which are vital at this very tender stage of hers and the baby's life. During pregnancy, she is also assigned to light household chores and is prohibited from lifting heavy objects.

3. When a woman is in her 6-8th months of pregnancy, family members, friends and relatives will start organizing schedules for inviting her to their homes for special lunches or dinners. During such gatherings a first-time would-be mother is advised or taught childbirth lessons - what to expect, what signs to be checked for or when to inform elders for a delivery and so on. These are usually women's affairs. A better prepared woman has a minimal risk of going into shock and a maximal chance for a successful delivery. Before hospitals were established, still now in rural areas, childbirth is performed by Chabokpi Maibis (mid-wives or nurses). They are community nurses and are usually experienced elderly women who insist on maintaining sterile conditions during child delivery. They are very successful.

4. After a child is born, the mother and baby are limited to a designated area in the house, which is warm or can be heated by a fireplace (for example, in the winter nights temperature in Manipur can drop down to 2-4 degrees C and they do not have electric heaters). The mother and baby stay in this area for 14 days. During this period, the maternal grandmother or an aunt will come to assist the mother in taking care of the baby, giving bath, changing diapers, washing baby cloths, etc. Even though relatives and friends visit the mother and her new baby, except for a good glance at the baby, no one, besides the mother and the caretaker, is allowed to hold the baby. This practice ensures that the baby is well protected from germs and infections. The visitors bring special food items for the mother, who is now in a restricted and a strict diet program. Oily and spicy foods are forbidden. All Manipuri mothers breast-feed their babies; therefore, a mother's diet includes a lot of fluid intake and various types of soups containing herbs and vegetables, and fresh fishes provide protein sources. Mother's milk contains all required nutrients for the child and maternal antibodies to protect the baby from diseases. The child needs nothing other than mother's milk at least up to 6 months until the Chak-Umba or Rice-Eating ceremony in which the baby test solid food for the first time.

A practice of shared breast-feeding observed in Manipuri society is an exciting and an interesting process. Sometimes a mother takes a few days to start lactating, i.e. to begin to produce breast milk. At this period a wet-mother (or a wet-nurse), who herself is breast-feeding her own child, will volunteer to feed the newborn for a few days. This practice of sharing of motherhood ensures a better chance for survival of every child born in the community during the earliest period of his or her life. Nowadays, formula substitutes are available and are widely used; however, in remote areas the above method of sharing of motherhood had been the most effective method.

5. The chances that a child will reach adulthood also depend on various social factors specially in rural areas where medical facilities and medicines are not readily available. Manipuri maibas (or medicine men) have an in dept knowledge of various medicinal plants, herbs and local animals. Some of the traditional methods of treatment are very effective against certain illnesses. The first three years of a child's life are the most fragile period since the body immune system (body defence mechanism against diseases) is not yet strong enough. Apart from the medicinal practices, social customs and ceremonies associated at various stages of development in a baby's life are also important. Four main stages of child development and ceremonies asssociated with them practiced in Manipur are briefly described. (i) Manipuris celebrate the birth of a child on the 6th day, a "Baby-Shower or a Welcome Ceremony" called "Epan Thaba" (Swasti-Puja or Ming-Thonba or naming of the child). Friends and relatives are invited, gifts are presented along with laining-laishon, meaning pujas. (ii) Next, parents and grandparents look forward to the day of Chak-Inba or Chak-Uma (rice-eating ceremony) in which the baby tastes solid food for the first time. Till now the baby had been living strictly on mother's milk or on a liquid diet. This too is a social gathering with Laining-Laison, and a feast for everybody. (iii) When the baby is about 3 years old, "Nahutpa or ear-ring ceremony" is performed with great festivity. This is performed both for boys and girls. I would presume that at this stage boys and girls think alike and that a boy can't tolerate a special ceremony for girls alone even though he removes his earings a few years later when he starts schooling. This is a gala festival for the child because at this age he or she enjoys a special attention awarded to them. (iv) When a child is ready to attend school (4-5 years of age), he/she is about to mingle with people outside his home away from parents and is starting a new adventure in life. "Mangol-Peeba or a blessing ceremony" is performed. Family and neighborhood elders are invited to bestow upon blessings on the child. The child bows his head in front of grandparents, parents and elders, and each person blesses the child Mangol (wisdom) and Punshi-Nungsang (longevity or full life). In this way, the life of a Manipuri child is celebrated and taken cared of by the whole community. Above all, "Ningol Chakouba" festival, in which women who were married to distant places come to her parents house along with the children for a sumptous feast and get-together (more or less similar to Thanksgiving in the US), helps to maintain the family ties forever. These functions bring a continuous attention and safeguard to the child while growing up in a hostile environment. It takes a village to raise a child - is a favorite phrase of Mrs. Hillary Clinton, the First Lady of the United States of America. Manipuri society is a good example.

Although Manipuri custom ensures a better chance for the survival of its children, the educational level of Manipuris is still low. At this electronic age of super highways, no longer Manipuris are isolated in the hills and plains of Manipur or in the valleys of Burma, Silchar, Guwahati and so on. The world is wide open for anyone to explore and opportunities to pursue. Higher education, while preserving the tradition, will insure a smooth and successful adaptation for all Manipuris to social changes carried with time, and to lead a successful life wherever they decide to live. Education empowers a person to choose profession, to gain respect from others, to strive for a brighter future and to bring up his/her child to a healthy adulthood.

Finally, the above narration on the traditional ceremonies is a recollection of my own experiences while growing up in Manipur. The protocol for each function mentioned above is elaborate, and I am not an expert on those subjects. I, therefore, will welcome any further elaborations or suggestions on the topics.

P.S. The above IMR data for India, unfortunately, have not changed much

according to a recent article published in National Geographic (October,

1998).